On the finish of a protracted street journey by way of rural China in 2009, American journalist Barbara Demick had an encounter that will change the course of her life. Within the earlier days, she had interviewed a number of mother and father whose kids had been forcibly faraway from them by authorities officers. Demick suspected there could also be a hyperlink between the lacking kids and China’s booming worldwide adoption trade.

She had sufficient for her story, however some intuition compelled her to observe the subsequent result in distant Gaofeng Village, excessive within the mountains of Hunan Province.

Her driver might solely take her to this point. The filth street ended at a stream, the place she was met by native girl Zanhua Zeng and her daughter Shuangjie. They guided her throughout a makeshift bridge and into the village the place “everything was in the process of falling down or going up”.

Zanhua Zeng and daughter Shuangjie, assembly Barbara Demick in a second that will change all their lives.

Barbara Demick

There, she learnt about two-year-old Fangfang, daughter of Zanhua and twin sister of Shuangjie, violently taken from her aunt’s care in 2002. Authorities officers had informed the household they had been in breach of China’s One Baby Coverage and weren’t allowed to maintain the child. They’d no concept what had occurred to their daughter and sister.

Zanhua’s parting phrases had been: “Come back again and next time bring my daughter.”

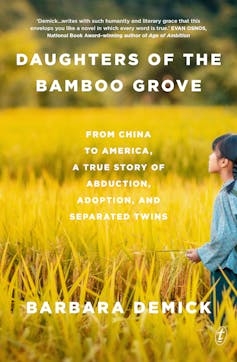

Assessment: Daughters of the Bamboo Grove: From China to America, A True Story of Abduction, Adoption, and Separated Twins – Barbara Demick (Textual content)

Extraordinary penalties

On the time, Demick had no premonition of the importance the Zeng household and their story would play in her life – and people of many others. However in writing a front-page report for the Los Angeles Instances concerning the hyperlinks between China’s stolen kids and worldwide adoptions, together with a small piece concerning the lacking twin Fangfang, she began a series of occasions with extraordinary penalties.

Fangfang (renamed Esther), within the referral picture provided by the orphanage.

For Zanhua and Shuangjie, it could ultimately result in a reunion with Fangfang, accompanied by Demick, who helped organise it. She was to develop an everlasting reference to the household – and with Fangfang’s adoptive American household, too.

Daughters of the Bamboo Grove does what the perfect tales do: humanises a giant subject. On this case, China’s one youngster coverage and the worldwide adoption trade it created.

Demick’s e-book is a narrative of China, and of incomprehensible authorities management. However as informed by way of this case of the separated twins, it’s additionally a narrative of household, id, loss and resilience.

It’s private and transferring, but additionally totally researched, strengthened with compelling and confronting statistics and anecdotes.

The twins’ assembly as younger ladies was documented by Barbara Demick for the Los Angeles Instances.

Demick outlines the inhabitants progress that led to the introduction of the One Baby Coverage in 1979 and the rise of the State Household Planning Fee, set as much as implement the legislation limiting most Chinese language households to 1 youngster.

“Family Planning morphed into a monstrous organization that dwarfed the police and military in manpower,” she writes. “By the 1990s, it was estimated that eighty-three million Chinese worked at least part-time for Family Planning.” (By comparability, China’s mixed armed forces had been estimated to quantity roughly three million on the time.)

The organisation was “intrusive in the extreme”, with feminine staff having to report once they had their durations and, in some instances, present their blood-stained sanitary pads. After giving beginning to their first youngster, ladies had been pressured to have an IUD or had been sterilised.

Individuals who violated the legislation acquired fines of two to 6 instances their annual earnings. If violators had been civil servants, they might lose their jobs. In rural areas, the place folks had been much less reliant on authorities jobs, the coverage was applied with “brute force”.

Individuals had been overwhelmed. Generally their properties had been demolished or set on hearth. “If you violate the policy, your family will be destroyed,” learn an indication on a wall not removed from the Zeng’s dwelling. Household Planning officers usually checked even probably the most distant villages, generally tipped off by neighbours.

If a girl was found to be pregnant after having a baby, she can be pressured to bear an abortion. The strategies had been “crude, often barbaric,” Demick writes. “Doctors would sometimes induce labor and then kill the baby with an injection of formaldehyde into the cranium before the feet emerged.”

Though Chinese language folks, significantly these from rural communities, usually wished to have greater households, that they had no energy to struggle the authorities. Those that tried to quietly subvert the system had been ruthlessly punished.

These practices had been so widespread, they had been usually accepted. However when authorities officers began to take infants from households who had defied the coverage, resistance grew. Different households began reporting instances like what had occurred to Fangfang. Household Planning had forcibly eliminated kids, refusing to supply any particulars about their whereabouts.

Officers miscalculated in 2005 once they dared to take a boy, Demick writes. He lived in a city, attended college and was not as poor as a few of the different affected households. The college made a criticism, which was supported by an area politician. The boy was returned to his household after 29 days.

Listening to about this case emboldened different households to mobilise and struggle again. These had been among the many first households Demick met when she travelled to cowl the story of the lacking kids in 2009.

Baby trafficking by ‘good Samaritans’

Chinese language infants had been in excessive demand for worldwide adoption, and it had turn into a profitable enterprise. One Hunan orphanage director later informed police they began a service to permit foreigners to undertake infants in 2001; they had been charged a US$3,000 money donation per child. In some instances, the infants genuinely wanted properties and households, Demick writes, however the cost was “in effect a bounty that incentivised a wave of kidnapping of female babies and toddlers”.

Shaoyang Social Welfare Institute, the place Esther spent the final six months of her life in China.

Barbara Demick

It steadily turned clear that most of the kids eliminated by Household Planning officers had been among the many wave of Chinese language infants and toddlers adopted by households from different nations, all of whom paid vital charges to take action, in addition to donating to the orphanages. It was later revealed that orphanages routinely fabricated details about how and the place the infants had been reportedly left.

By the point Demick’s experiences had been printed in 2009, almost 100,000 infants had been despatched out of China, greater than half to the US. The worldwide quantity would attain 160,000 by 2024, when China ended its worldwide adoption program.

Demick’s story about stolen infants, plus different experiences from inside China and elsewhere, surprised the worldwide adoption group and fogeys of Chinese language adoptees around the globe. Till then, China was perceived to be probably the most moral alternative for worldwide adoption. For adoptive mother and father who now feared their adopted kids may very well be taken from them, the revelations had been terrifying, Demick says.

Marsha and Esther (background) of their Texas kitchen.

Barbara Demick

One in every of these mother and father was a Texan ladies named Marsha. She and her husband Al had adopted two Chinese language women: Victoria in 1999 and Esther in 2002. By way of creating connections amongst households who had adopted from China, Demick got here throughout Marsha – and realised Esther could also be Fangfang: the lacking twin.

She was appropriate. Nonetheless, the story was removed from resolved, which explains, partly, why Demick had loads of materials for her e-book.

Reporter as dogged detective

Daughters of the Bamboo Grove is a testomony to dogged reporting. Demick’s expertise as a researcher, interviewer – and successfully, a detective – imbue the e-book with substance and credibility.

She handles tough subject material sensitively, portraying the Zeng household in China and adoptive mom Marsha within the US with empathy. She acknowledges the challenges they confronted and recognises their devotion to their kids.

Her descriptions of the dual sisters, Shuangjie and Esther, are perceptive and delicate. Restraint is a strong writing software and Demick makes use of it right here to nice impact.

That is the second the place the twins first meet, exterior the Zeng household dwelling in China:

When everyone was out of the van, the 2 of them stood subsequent to one another, facet by facet, dealing with the photographer. No one embraced. No one spoke. I imagined the twins as bride and groom in an organized marriage, assembly for the primary time, prepared to pose for the photographer however not but in a position to interact in dialog.

Twins Esther (left) and Shaungjie, separated most of their lives, meet for the primary time since babyhood.

Barbara Demick

Demick got here to this story with the views and limitations of an American journalist, however has gone to outstanding lengths to listen to and convey the voices of Chinese language folks impacted by the One Baby Coverage.

On the identical time, she challenges Western paternalistic concepts round adoption, questioning the view expressed by many she encounters that the Chinese language kids adopted by Westerners had been fortunate, assured to have higher lives elsewhere.

China’s One Baby Coverage was not formally abolished till 2015. In its 35 years, it did virtually unimaginable harm, concludes Demick:

the coverage shattered marriages, led to the deaths of numerous kids and suicides of fogeys, and left China with a inhabitants anticipated to proceed declining into the subsequent century. It was all encompassing, leaving virtually everybody a sufferer or perpetrator or each.

For the a whole lot of 1000’s of youngsters despatched out of China throughout this era, the legacy of One Baby endures. As Demick writes, they’re

residents of their adopted nations however tethered by blood to a different household and nation they battle to understand. Dwelling on this in-between house between worlds.

In dedicating Daughters of the Bamboo Grove to Chinese language adoptees around the globe, Demick says she hopes in some small manner it helps them to know the place they got here from, and the way they obtained to the place they’re right now.