In Woman on Woman, journalist Sophie Gilbert crafts a compelling narrative about how films, TV, celebrities and pop stars assemble a tradition that encourages girls to internalise misogyny – and even rewards them for it. She traces how this manifests over time, from the Nineties to now, by the sexualisation of younger women in teen “sex” comedies, actuality TV makeovers, the mainstreaming of pornography and extra.

The guide is a helpful primer on how largely white, American-centric well-liked tradition makes girls’s exploitation commonplace.

It strikes swiftly between examples, which could possibly be complicated for readers unfamiliar with the totally different worlds inhabited by numerous figures. They embrace socialite and early actuality star Paris Hilton; musician Amy Winehouse, who made headlines together with her dependancy challenges; and “riot grrrl” feminist rocker Kathleen Hanna.

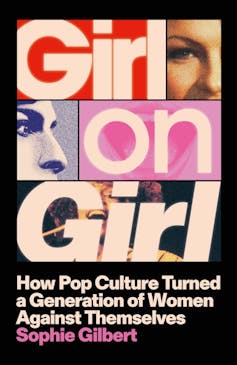

Woman on Woman: How Pop Tradition Turned a Era of Ladies Towards Themselves – Sophie Gilbert (John Murray)

Woman on Woman doesn’t essentially break new floor. It does, nonetheless, convey collectively disparate strands of our cultural dialog, largely counting on current analysis and cultural commentary. Western well-liked tradition, it argues, gives girls with a slim set of beliefs.

Gilbert’s guide depicts well-liked tradition as a car for instructing girls what sorts of behaviour are acceptable and fascinating. These classes are packaged in alluring parcels, just like the Actual Housewives, Lindsay Lohan, Britney Spears and Pamela Anderson. Gilbert cleverly attracts a line from Madonna as provocateur to the hatred of ladies oozing from early 2000s rom-coms, the TikTok Trad Wives and Hillary Rodham Clinton’s failed presidential bids.

Within the guide’s early pages, Gilbert exhibits how Hanna’s punk slogan of “Girl Power” was “appropriated” by the Spice Ladies (who she describes as “sexy women who behaved like toddlers at a wedding”) in 1996. Within the course of, “Girl Power” went from signalling a motion charged by anger at “diminishment and abuse”, to a feminism of particular person empowerment that “made you want to immediately go shopping”. It was then “almost instantly appropriated by brands”.

The Spice Ladies, ‘sexy women who behaved like toddlers at a wedding’, appropriated the riot grrrl slogan of ‘Girl Power’.

Doug Kanter/AAP

Packaging empowerment

In style tradition could seem fluffy and inconsequential, however Gilbert emphatically connects it to the fabric penalties of misogyny. This contains the rolling again of abortion rights in the USA, the election of alt-right males who overtly despise girls and the normalisation of gendered harassment, violence and abuse.

Gilbert persuasively argues “popular culture is a strikingly predictive and transformative force with regard to the status of women and other historically marginalised groups”.

It’s not simply that ladies are routinely degraded and dehumanised for leisure. It’s that this merciless spectacle has been normalised over many many years – and has been packaged and offered as empowering and “good for women”.

Gilbert attracts connections between the exploitation behind supermodel Kate Moss’s rise to prominence within the Nineties (she was bullied into posing for topless images), the ritualised humiliation of early 2000s actuality TV and the 2010 publication of “crotch shots” of an 18-year-old Miley Cyrus. In doing so, she charts the various methods well-liked media normalises girls’s exploitation.

Kate Moss felt ‘vulnerable and scared’ in her topless Calvin Klein advert, with Mark Wahlberg.

GettyImages

Her investigation complicates the seemingly easy and empowering facade of those fashions of femininity. For example, the stylist for Moss’ 1990 topless shoot for The Face journal cowl that launched her to fame remembers it as “fun” and “instinctual”, whereas many years later, Moss recollects crying when coerced into taking her high off.

She additionally remembers feeling “vulnerable and scared” through the 1992 topless Calvin Klein shoot with Mark Wahlberg. “I think they played on my vulnerability,” she mentioned.

Woman on Woman successfully interprets the concepts feminist students have been unpicking for many years. Its sustained and considerate engagement with these concepts is what distinguishes it from related books of journalism on the gender politics of well-liked tradition.

A typical limitation of such books is the false assumption that these concepts are new. Nonetheless, Gilbert weaves collectively Rosalind Gill’s postfeminism as a sensibility, Brenda Weber’s work on makeover TV and Kate Manne’s theorisation of misogyny with well-liked media examples.

In a chapter on the not possible expectations of latest femininity, Gilbert applies Gill’s idea of “midriff advertising”, or “low-slung hipster jeans and ten inches of tanned, taut stomach”, to 2000s “it-girl” Nicole Richie. She explains how she was variously shamed for being too fats after which too skinny. This led, Gilbert writes:

to her elevation in standing from Paris’s sassy sidekick to size-double-zero aughts trend emblem, a frail, childlike determine whose equipment had been so massive they threatened to topple her.

Paris Hilton and ‘sassy sidekick’ Nicole Richie, who was variously shamed for being too fats and too skinny.

Damian Dovarganes/AAP

Feminism: all over the place and nowhere

Gilbert’s guide shouldn’t be wholly damaging. She additionally charts the rise (and infrequently fall) of those that push again in opposition to the established order.

In a chapter on “confessional auteurs”, she considers Ladies creator Lena Dunham. In one other, which considers excessive, violent intercourse in artwork, she appears to be like at French filmmaker and novelist Catherine Breillat. In Breillat’s 1999 movie, Romance, a few younger lady “driven almost to madness” by her boyfriend’s refusal to have intercourse together with her, Gilbert writes:

Breillat phases what she appears to know as stereotypical male beliefs – a girl determined for intercourse, a girl sure and gagged – and renders them in ways in which make them each psychologically explosive and wholly unsexy.

Within the closing chapter on “rewriting the path towards power”, she explores the affect of latest feminist-leaning TV, equivalent to Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag and Michaela Coel’s I Could Destroy You.

Quite than ignoring feminism’s paradoxes and inconsistencies, Gilbert leans into how it’s directly all over the place (in commercials, behind Beyoncé on the VMAs, on t-shirts) and nowhere (rendered toothless, depoliticised, neoliberal).

Beyonce’s 2014 Video Music Awards efficiency in opposition to an enormous FEMINISM signal was a memorable cultural second.

Jason LaVeris/FilmMagic/GettyImages

Gilbert thoughtfully teases aside the contradictions and schisms in girls’s tradition (each well-liked and on a regular basis) to think about the combined messaging round sexuality, empowerment, femininity and success.

The problem of interrogating influential celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Taylor Swift is that they have a tendency to embody excessive variations of idealised femininity. Their our bodies are directly an instrument of their work and a canvas, on which a lot is projected. Culturally, they uphold and promote very slim concepts of heterosexual desirability, perfection and wonder.

Gilbert grapples with how the elevation of magnificence as a defining female advantage leads to fats shaming and trend policing of on a regular basis girls. Discussing the Kardashian-Jenners, she writes:

Their continuously altering faces and our bodies current the human kind as a perfectible venture able to be molded and painted and tucked in any manner that may encourage engagement and promote merchandise.

Kim Kardashian’s ‘constantly changing’ face and physique presents the human kind as a perfectible venture.

Doug Peters/STAR MAX/AAP

It’s exhausting to take a look at the rise in cosmetic surgery procedures and the prevalence of weight-loss remedy utilization and never blame celebrities, actuality TV and social media influencers. However these girls didn’t create this world, they only found out how to achieve it. Ought to we count on them to dismantle the system that empowers them?

Gilbert’s guide zeroes in on how well-liked feminist considering expects girls to vary, somewhat than programs. The accountability for inequitable establishments – like unpaid parental go away, restricted reproductive healthcare and hostile work cultures – is moved onto particular person girls to unravel. They’re anticipated to bear the burden, somewhat than society being anticipated to put money into systemic change. For example: paid parental go away, reasonably priced accessible healthcare and employment quotas.

The consequences are twofold, absolving institutional accountability and inscribing narcissistic, individualistic methods of considering.

Consuming our strategy to enlightenment

Woman on Woman circles round, however by no means instantly takes on a vital query: ought to we count on well-liked tradition to do the work of feminism? Can we devour our strategy to equal pay, reproductive rights, freedom from violence and respect within the office? We’re inspired – by well-liked media itself – to suppose so.

There are seemingly infinite articles that canonise “feminist TV shows and moments” that “every woman needs to watch”. They encourage viewers to consider themselves as “pop culture-loving feminists”.

That is significantly outstanding throughout on-line media aimed toward girls. It views content material by the lens of feminism and curates “feminist popular culture” as a recognisable class. That is used to inform us modern audiences can – and will – be feminist customers.

The thought of consuming our strategy to enlightenment has been offered to us on a number of fronts. But feminism was by no means mainstream. From its early days to now, it has been a scrappy insurgency.

The prominence of “girl power” and “girl bosses” could have lulled us right into a false sense of safety, however circumstances for girls (globally and regionally) nonetheless want bettering.

Regardless of its limitations, we want feminism in media and on a regular basis tradition. Kristen Stewart just lately mirrored, on her directorial debut at Cannes: “having a female body is an overtly political act, if you can get out of bed in the morning and not hate yourself”.