Florence Nightingale is commonly described because the founder of contemporary nursing. She was immortalised in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1857 poem, Santa Filomena: “A noble type of good / Heroic Womanhood.” For over a century, she has been remembered as “the lady with the lamp”, transferring via the wards of conflict hospitals.

In Laura Elvery’s debut novel, Nightingale, she is one thing else completely. She shouldn’t be the image, however the girl – not solely the caregiver, however a affected person, little one and sister. It opens with an epigraph from T.S. Eliot’s Little Gidding:

We will not stop from explorationAnd the tip of all our exploringWill be to reach the place we startedAnd know the place for the primary time.

This concept of seeing the acquainted in a brand new gentle mirrors the novel’s construction and spirit. Nightingale shouldn’t be a linear biography, nor an in depth account of Nightingale’s public accomplishments. It’s a quiet meditation on reminiscence, and on care and the methods it marks a life.

Evaluation: Nightingale – Laura Elvery (UQP)

Loss of life from poor hygiene and neglect

The novel is advised in three components throughout two timelines. It opens in Mayfair, London, in 1910. Florence is 90, frail and near dying. Her housekeeper, Mabel, watches over her as she drifts between moments of lucidity and reminiscences of her previous. The determine who as soon as helped to remodel navy hospitals displays on her frailty, and on Mabel’s look after her. She recollects her previous directions:

Use a transparent, agency voice so the affected person hears you the primary time. Don’t ask a affected person to show their head in the direction of you. Let the sunshine in. Ventilate the room. Clear the utensils. Change the sheets your self and do it rapidly, with out remark.

Florence Nightingale.

Henry Hering, Nationwide Portrait Gallery/Wikipedia

These instructions replicate Nightingale’s ethos: that dying got here not solely from bullets, however from poor hygiene, an infection and administrative neglect. Elvery hints at Nightingale’s broader impression – her work on sanitation, hospital reform and information assortment – not via exposition, however via the quiet authority of her voice and the awe she instructions amongst medical doctors, nurses and troopers alike.

On her remaining day, Nightingale receives a go to from Silas Bradley, a former soldier whose presence unsettles each her and the reader. As Half One ends, Silas asks, “What did Jean do to me?” The query will proceed to hang-out the novel.

Jean Frawley, a younger nurse serving beneath Nightingale (or “Miss N”) through the Crimean Struggle (1853–56), is launched within the novel’s second half. In Marseilles, on her option to Scutari, Jean meets Silas. Their temporary encounter units up a romantic subplot that runs all through.

However this thread can also be one of many novel’s weakest. Jean is launched as succesful and competent, however her story turns into dominated by her emotions for Silas. Her eager for him appears out of proportion and out of step with the extra grounded scenes surrounding it. The emotional arc feels much less earned, in comparison with the stark realism of the hospital scenes.

Laura Elvery hints at Florence Nightingale’s wider impression via the awe she instructions amongst medical doctors, nurses and troopers.

Joe Ruckli/UQP

Vivid hospital scenes

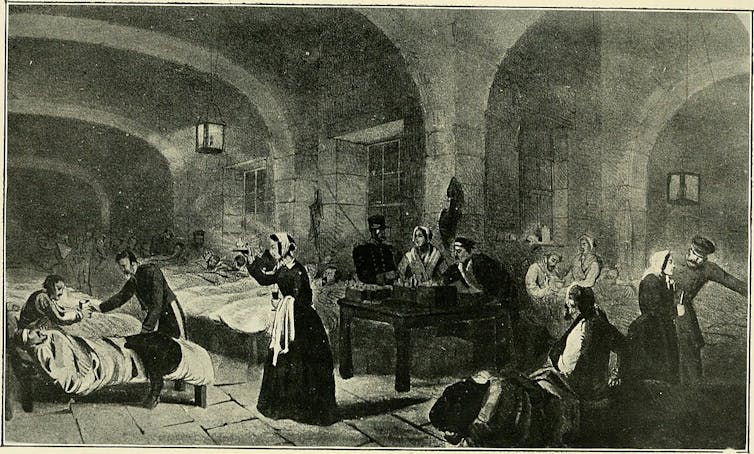

The main focus quickly shifts to Scutari (half of what’s now Istanbul) in 1854, and an overcrowded, filthy and overwhelmed hospital. That is the novel’s strongest part: vivid, harrowing and sharply noticed.

Jean’s voice brings urgency to the on a regular basis horrors she witnesses: “Whimpering men lay on stuffed sacks on every side of every corridor, keeping company with the rats, the roaches, the maggots.” Provides are quick, medical instruments are rudimentary, nurses are exhausted. The lads are dying. On this world, care is emotional work.

Elvery, recognized for her short-story collections Strange Matter and Trick of the Gentle, brings a lyrical, sensory type to those scenes. Her descriptions are wealthy with visceral, sensory element of rats, maggots, blood and chloroform.

Nightingale’s strongest part is ready in ‘an overcrowded, filthy and overwhelmed hospital’.

Wikimedia Commons

However the focus isn’t on historic accuracy for its personal sake. Elvery is extra within the interiority of her characters, within the psychic and bodily toll of caregiving. She doesn’t dwell on dates or battles. As an alternative, she focuses on what caregiving looks like: its price, its mess and its unusual intimacy.

They requested the ladies to kiss them, to write down for them, to inform them jokes […] One soldier requested Jean to breathe in time with him.

Probably the most transferring scenes comes after the conflict, in 1861, when Jean visits a Crimean Struggle memorial in London. She sees “on a plinth, the figure of a cloaked woman […] arms outstretched”.

Jean expects to really feel pleasure or recognition. As an alternative, she finds the statue unfamiliar. “Perhaps it was a goddess,” she thinks, noticing the “haloes of leaves that circled her wrists.” She recollects the phrases of the tailor who offered her her uniform: “Women can’t imagine that sort of suffering.”

The scene captures a key query within the e-book: who’s remembered, and in what type?

Resisting mythmaking

Elvery resists mythmaking. Her Nightingale shouldn’t be a saint, however a girl cast in complexity: good, cussed, typically troublesome. The novel invitations us to see her not as a logo, however as an individual formed by sickness, want, ache and time. Nightingale isn’t just a novel about Florence Nightingale, or about nursing. It’s concerning the bodily and emotional labour of care, and the folks whose work usually goes unnoticed.

Half Three returns to 1910 and Nightingale’s remaining moments. However Nightingale shouldn’t be the centre of her personal story. Jean’s narrative kinds the novel’s emotional core, and her connection to Silas drives extra of the plot than Nightingale’s recollections. On this means, Elvery shifts focus, each structurally and thematically, away from a single determine – and towards the quieter, usually invisible work of caregiving itself.

In a time when the price of care – whether or not in hospitals, properties, or conflict zones – is so seen, Nightingale feels well timed. Elvery asks what it means to nurse, and to be nursed. Her novel honours the messy, human particulars of caregiving, even because it gestures towards the legacy of a girl who reshaped its very foundations.