Our cultural touchstone sequence appears to be like at works which have had an enduring affect.

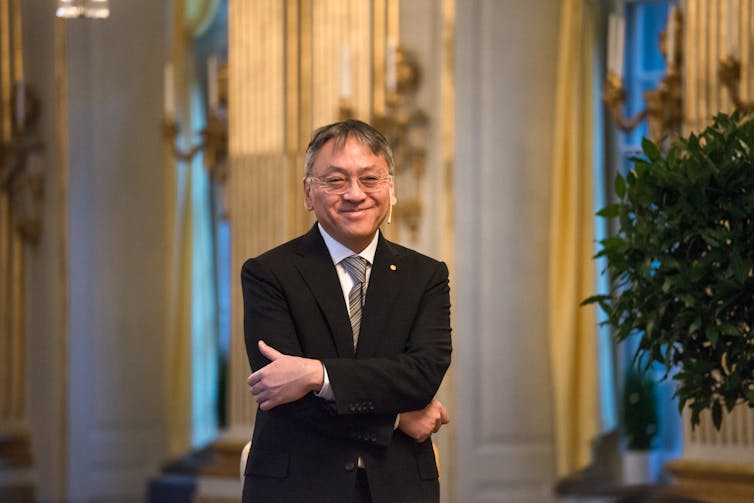

Kazuo Ishiguro’s By no means Let Me Go was revealed 20 years in the past. Since then, the Japanese-born English author has been awarded the Nobel Prize in 2017 and knighted for providers to literature in 2018.

By no means Let Me Go has been translated into over 50 languages. It has been tailored into a movie, two stage performs, and a ten-part Japanese tv sequence. A important and business success, the novel has been reissued in an anniversary version with a recent introduction from the creator.

A spate of reappraisals has accompanied this anniversary: “An impossibly sad novel […] it made me cry several times […] sadness spilled off every page.” “No matter how many times I read it,” one critic wrote, “Never Let Me Go breaks my heart all over again.”

These transient excerpts are clear: the novel pulls us right into a morass of unhappiness that by no means lets us go. “I’ve usually been praised for producing stuff that makes people cry,” Ishiguro has mentioned. “They gave me a Nobel prize for it.”

Unusual and acquainted

I need to rethink the emotional cost of By no means Let Me Go.

The deluge of tears attested to by critics hinges on the connection Ishiguro meticulously crafts between narrator and reader. That is initiated within the novel’s first traces. Ishiguro locations us in another Nineteen Nineties England. His opening gambit will likely be acquainted to novel readers:

My identify is Kathy H. I’m thirty-one years previous, and I’ve been a carer now for over eleven years. That sounds lengthy sufficient, I do know, however truly they need me to go on for an additional eight months […] My donors have all the time tended to do significantly better than anticipated.

Inside a number of pages, the narration slips into Kathy’s recollections of her idyllic Nineteen Seventies youth at a boarding college known as Hailsham. We’re immersed in a childhood world of friendship and exclusion, jealousy and love. It is a recognisable world. Ishiguro’s first-person narration affords the reader vicarious entry to Kathy’s inside tangle of emotion, want and reflection, such that we will recognise one thing of ourselves in her.

But one thing is amiss in her narration. Flat and somewhat affectless, it’s a decidedly much less curious, much less passionate and extra tempered mode of narration than we would count on. The threadbare texture frays the narrative world. What are we to make of the opaque references to “carer”, “they” and “donors”?

This uncanny rigidity between the unusual and the acquainted simmers till a 3rd of the way in which by means of the novel, when a “guardian” at Hailsham reveals the scholars’ futures:

Your lives are set out for you. You’ll turn into adults, then earlier than you’re previous, earlier than you’re even middle-aged, you’ll begin to donate your very important organs. That’s what every of you was created to do.

Good liberals

Kathy is a clone, condemned to demise so her organs could be harvested for “normals”. That this heartless system “reduces the most hardened critics to tears” comes as no shock. In spite of everything, Ishiguro has evoked the acquainted style of the Nineteenth-century boarding-school bildungsroman to encourage us to consider that it is a type of subjectivity we will share. This bildung – the German phrase for “formation” – isn’t an integration into society however somewhat a dismemberment by society.

That this doesn’t provoke anger, in readers and characters alike, does come as a shock. For if the proclamation of the scholars’ fates isn’t distressing sufficient, Ishiguro forces us to confront the clones’ response or, somewhat, the shortage thereof. There are not any incandescent flashes of fury and even gentle expressions of dismay.

As an alternative, the clones are “pretty relieved” when the speech stops. Information of their impending demise passes them like a ship within the evening, inciting “surprisingly little discussion”. On this disconcerting silence, the relation between reader and clone is mediated by means of one other style: science fiction.

The bildungsroman and science fiction, identification and misidentification, intimacy and estrangement – these are the instruments of Ishiguro’s commerce. He manipulates them, and us, with precision. There’s intimacy as we recognise that the scholars’ on a regular basis lives – studying novels, creating artwork, enjoying sport – are very similar to our personal. There’s estrangement as we realise that the clones are willingly cooperating in their very own deaths. They’ll “donate” and “complete” within the narrative’s chilling phrases.

In different phrases, we cry as a result of the clones are similar to us, however our anger in the direction of the equipment of donation is blunted as a result of the clones will not be but us, in that their complicity eerily lacks our intuition for self-preservation.

Assured that we’ll take ourselves because the measuring stick, Ishiguro compels us to undertake a place of superiority characterised by a paternalistic ethos of sympathy and care. On this manner, he persuades us to learn pretty much as good liberals. We acknowledge the humanity of the clones and embrace the range of our frequent situation. On the identical time, we’re complacent within the data that we’re nearly the identical, however not fairly. We’re insulated by a disavowed distinction.

An summary formal equality, evacuated of concrete historic content material, is exactly what’s expressed when the identical critics who reward the novel’s melancholic tone declare that Ishiguro exhibits us “what it is to be human” or that he enlivens this in any other case “meaningless cliche”.

Kazuo Ishiguro in Stockholm to obtain the Nobel Prize in Literature, December 2017.

Frankie Fouganthin, through Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Past liberal sentiments

Is Ishiguro doing something greater than providing a banal endorsement of frequent humanity? It appears to me that he’s, and in doing so he’s summoning our liberal sentiments solely to show them towards us.

The mechanism he makes use of is as previous because the novel kind itself: the romance plot. Romance results in the happily-ever-after of marriage: an ideal union by which every particular person completes the opposite.

Not lengthy after we be taught that Kathy and her associates are clones destined to die, we turn into aware about a hearsay: college students who can show they’re “properly in love” are eligible for a “deferral” of their donations. To fast-forward by means of the novel’s tangled romance plot to the denouement, Kathy and Tommy – a fellow clone – observe down Hailsham’s former administrator to plead their case. Not solely is their request for deferral rejected, however the potential for deferral is dispelled as a pernicious hearsay.

The attract of romance has been a lure, a chilly metal entice within the guise of a heat embrace. Ishiguro dangles the promise of romance solely to show its sinister echoes within the donation system.

The “completion” of romance is macabrely inverted. Completion by means of matrimonial union with a perfect different is reworked into the “donation” of organs, which completes an unknown “normal”, whose life can proceed on account of the clone’s demise.

Cowl of the primary version of By no means Let Me Go (2005)

Ishiguro positions us in order that we’re unwittingly aligned with the “normal” inhabitants, whose “overwhelming concern was that their own children, their spouses, their parents, their friends, did not die from cancer, motor neuron disease, heart disease”.

What we would like the clones to do (resist their fates) and the technique of doing so (romance) are revealed as answerable for the donation system. If we would like Kathy and Tommy to reside as a result of they love one another – and we do as a result of Ishiguro has compelled us to take care of them – then we’re endorsing the logic that designates them as disposable within the first place.

The anger Ishiguro has intentionally blunted returns, redoubled. Our care is reworked into complicity. We, somewhat than the clones, are the targets of Ishiguro’s ire.

Translating this into political phrases, Ishiguro is giving aesthetic kind to neoliberalism’s eclipse of liberalism. It’s no coincidence that By no means Let Me Go takes place in England between the Nineteen Seventies and Nineteen Nineties, the precise interval of neoliberalism’s emergence and consolidation.

However that is no easy transition. By no means Let Me Go implies that liberalism is the ghost within the neoliberal machine. The novel is a illustration of a vicious neoliberal class system, the place those that can afford alternative components can substantiate the fantasy of liberal individualism, whereas those that can’t function alternative components.

On this sense, Ishiguro could be learn as posing a sequence of incisive questions, not merely providing the platitude that we’re all human. What are the prices of affection? Why is there a trade-off between caring for these near us and caring for many who are distant? How do our claims of shared humanity pave the way in which for domination? Why can we assume that our lifestyle is superior as a result of it’s predicated on liberal ideas? How can we break from a callous system by which we too are complicit?

Twenty years on, these questions are as related as ever. To start answering them, maybe we have now to wipe the tears from our eyes and switch to anger.