Within the thrilling finale of the TV collection The People, set throughout the Reagan administration, deep-cover KGB operatives Philip and Elizabeth Jennings are confronted with a troublesome choice. Posing as an abnormal American married couple, for many years they’ve raised youngsters, filed tax returns and slipped effortlessly into the rhythms and routines of on a regular basis suburban existence in Washington, D.C.

All of the whereas, they’ve been spying – gathering intelligence and surreptitiously feeding it to their communist masters in Soviet Moscow. Now, with the FBI closing in and their cowl on the point of collapse, they have to determine whether or not to remain and face arrest or flee the nation they’ve come to name dwelling. There’s additionally their teenage youngsters to think about.

The story appeared too unbelievable to be true – however actually it was based mostly partially on Donald Heathfield and Ann Foley, subsequently outed as Andrei Bezrukov and Elena Vavilova, a Russian couple who had spent greater than 20 years masquerading as Canadians. On the time of their unmasking, they had been residing quietly in the USA with Tim and Alex, their two sons.

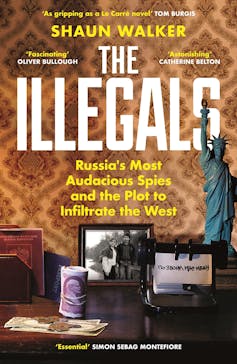

Evaluate: The Illegals: Russia’s Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West – Shaun Walker (Profile)

A brand new e-book, The Illegals, tells of a community of Russian brokers working throughout the US, throughout the late twentieth and early twenty first centuries – together with Bezrukov and Vavilova. It opens with their dramatic 2010 arrest, a part of ten Russian spies (principally illegals like them) detained by the FBI.

Writer Shaun Walker, the Guardian’s central and japanese Europe correspondent, attracts on declassified archival materials and first-hand interviews. The result’s an engrossing, eye-opening account of the key world of the Soviet “illegals programme”: embedded spies who lived surreptitiously within the West with out the security blanket of diplomatic safety.

The TV present The People was based mostly partially on Donald Heathfield and Ann Foley (aka Andrei Bezrukov and Elena Vavilovo).

Marvin Joseph/The Washington Publish/Getty Photographs

As Walker explains, “legals” had been Russian operatives working beneath official cowl – as diplomats or embassy workers, aware of diplomatic immunity. Against this, “illegals” operated off the grid. They crept silently into Western international locations beneath false identities, usually stolen from the lifeless. This made them tougher to detect, however left them way more susceptible if uncovered.

One of the vital high-profile figures within the 2010 spy bust was Anna Chapman. Not like many different illegals, Chapman didn’t even hassle to disguise her Russian identification. As a substitute, as Walker recounts, she entered America utilizing a British passport – acquired by means of a short marriage to a UK citizen – and labored as a New York actual property dealer.

Her photogenic appears to be like and media-friendly persona made her the general public face of the scandal. After being deported, Chapman reinvented herself as a tv host, runway mannequin and pro-Kremlin influencer.

After the 2010 spy bust, Anna Chapman grew to become a TV host, runway mannequin and pro-Kremlin influencer.

Alexander Nemenov/AFP/GettyImages

The actual People

Walker outlines how Bezrukov and Vavilova first met within the early Nineteen Eighties, as historical past college students in Siberia. There, KGB “spotters” recognized them for potential recruitment. Later, he provides,

they progressed to an arduous coaching programme lasting a number of years, moulding their language, mannerisms and identities into these of an abnormal couple. They left the Soviet Union individually in 1987, staged a gathering in Canada, and started a relationship as if they’d simply met.

Having married beneath their assumed names, Andrei and Elena adopted the habits and customs of an abnormal middle-class life. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the couple had been reduce off from Moscow, however by the top of the last decade they had been reactivated by the SVR, Russia’s new international intelligence company. Round this time, Andrei gained a spot at Harvard’s Kennedy Faculty, permitting the household to maneuver to Massachusetts and combine additional into American society.

The house of alleged spies Donald Healthfield and Ann Foley once they had been arrested in 2010.

Nancy Lane/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald/Getty Photographs

As Andrei networked in tutorial and coverage circles, Elena maintained the phantasm of home normality, fashioning herself as a doting “soccer mom”, elevating the youngsters and protecting home. In the meantime, she was secretly decoding encrypted radio messages within the again room.

This went on for years. Then, sooner or later, an surprising knock on the door as they celebrated their son Tim’s twentieth birthday introduced the charade crashing down. FBI brokers burst in, handcuffed the couple in entrance of their sons and marched them out into the road.

Quickly after their arrest, Andrei and Elena had been deported to Russia in a high-profile spy swap. They had been awarded state honours by Vladimir Putin and briefly grew to become minor celebrities in Moscow. Their sons, each born in Canada, had been left reeling.

In 2016, Walker tracked the sons down for a bit he was writing for The Guardian: they had been within the means of suing the Canadian authorities to have their citizenship reinstated, having been stripped of it when all the things kicked off. In 2019, a court docket dominated Tim and Alex (who was 16 when the FBI arrested his mother and father) might maintain their citizenship. Each insisted they’d recognized nothing about their mother and father’ espionage work.

Alex Valivov, son of Russian ‘illegal’ spies disguised as People, talked to the media after he gained a court docket bid to maintain his Canadian citizenship.

Putin ‘beside himself’

As Walker recounts, the raid had been coordinated by then-FBI director Robert Mueller. It had been timed to keep away from derailing a fastidiously deliberate diplomatic summit.

In 2009, Barack Obama launched a high-profile “reset” of relations with Russia. Obama wished to woo Dmitry Medvedev – a reasonable political figurehead standing in for Putin, who remained the true energy behind the scenes in Russia.

A deliberate summit in Washington meant to cement the spirit of renewed cooperation. However as the dimensions of Russia’s covert operation grew to become obvious, the White Home was confronted with a dilemma: tips on how to reply with out jeopardising the reset.

In accordance with Walker, Obama was irked by the entire state of affairs. He quipped that it felt like one thing out of a John Le Carré novel. Finally, a compromise was reached: the arrests would occur, however solely after Medvedev’s go to, in order to not trigger undue embarrassment.

Intrigued by this “twisted family story”, Walker began to look into the illegals enterprise in better depth. He rapidly realised “there was nothing quite like it in the history of espionage”. At occasions, varied intelligence businesses had deployed operatives as international nationals, “but never with the scope or scale of the KGB programme”.

Obama felt just like the raid on the Russian ‘illegal’ spies was like one thing out of a John Le Carré novel.

Andrew Harnik/AAP

A century of dramatic, bloody historical past

The illegals had been, in Walker’s reckoning, one thing uniquely Russian, rooted within the nation’s advanced historic expertise. The extra he learn, the extra he got here to view the programme as a lens by means of which he might “tell a much bigger story, of the whole Soviet experiment and its ultimate failure, a century of dramatic and bloody history”.

To grasp how the illegals venture happened, Walker winds the clock all the way in which again to 1917, when the Bolsheviks seized energy – and espionage grew to become a cornerstone of the nascent Soviet state. He reminds us whereas Lenin and his comrades had gained formal management of the nation, “they still faced the colossal task of implementing and retaining it across the vast Russian landmass”.

Gripped by his perception within the predictive rules of historic materialism,

Lenin was certain that state establishments would ultimately wither away, the evolving employee’s paradise rendering them meaningless. Nevertheless, to realize this completely satisfied finish level, he believed an interim interval of ruthless state violence was required.

The Cheka: precursor to the KGB

This helps to elucidate why he established the Cheka, a secret police pressure tasked with crushing counterrevolutionary exercise and implementing Bolshevik rule. At its head was Feliks Dzerzhinsky, a fanatical Polish ideologue who had spent years in Siberian exile. Removed from a brief measure, the Cheka “quickly grew to a huge fighting force that could be unleashed on political and class enemies”, Walker writes.

Feliks Dzierzynski was the pinnacle of the Cheka, the Russian secret police pressure that preceded the KGB.

Wikimedia Commons

The Cheka was an essential participant within the Russian Civil Battle, which pitted Lenin’s Reds towards the Whites – a free alliance of pro-tsarist regiments and international mercenaries, usually united by little greater than their implacable hatred of Bolshevism. The state of affairs on the bottom was chaotic and unpredictable; either side engaged in ruthless violence.

Right here, on this blood-drenched crucible, the Bolsheviks honed their clandestine strategies – konspiratsiya (subterfuge) – perfecting the usage of disguises, false identities and underground communication. In areas the place the Whites gained a territorial foothold, brokers had been ordered to remain behind and coordinate resistance, laying the groundwork for what would change into the illegals programme.

When the Bolsheviks emerged victorious in 1921, the Cheka was not disbanded – however repurposed. The follow of planting operatives deep inside enemy strains survived the battle and expanded in scope. Lenin’s thought of mixing authorized diplomatic work with unlawful undercover infiltration grew to become a defining function of how the Soviet Union would run its intelligence companies for the subsequent 70 years.

Stalin’s secret police

Below Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin, the key police was reworked into an all-encompassing instrument of surveillance, repression and domination.

Purges consumed the get together. Ideological fervour curdled into present trials and murderous terror. And paranoia grew to become an organising precept of Soviet political life. The demand for vigilance intensified – not simply at dwelling, the place informants and denunciations grew to become routine, but additionally overseas. Actual and purported enemies had been seen lurking within the democratic establishments of the West.

Ironies abound right here. The very strategies that helped to maintain the early Soviet state – secrecy, trickery, duplicity – quickly grew to become grounds for suspicion on Stalin’s watch. The technology of illegals educated and embedded throughout the Nineteen Twenties and early Thirties had been amongst these earmarked for liquidation, Walker writes. Stalin, ever cautious of plots towards him, got here to view his personal spies as potential traitors.

He ignored – or wilfully dismissed – a lot of the intelligence they’d risked their lives to assemble, usually with disastrous penalties. When advance warnings of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s secret plan to betray Stalin and launch a large invasion of the Soviet Union, landed on his desk in 1941, as an example, they had been waved away as provocation or outright fabrication. In some instances, he had his spies tortured or shot. Loyalty was no protector towards paranoia.

Dmitry Bystrolyotov was a legend in Soviet intelligence circles.

Alchetron

Among the many casualties was Dmitry Bystrolyotov, who Walker describes as “perhaps the most talented illegal in the history of the programme”. A very chameleonic determine, Bystrolyotov was a dashing and multilingual agent whose exploits in Western Europe made him a legend in Soviet intelligence circles. “His speciality was the recruitment of agents who had access to diplomatic codes and ciphers,” the Russian scholar Emil Draitser attests, “and his modus operandi involved women”.

By way of a collection of painstakingly crafted affairs, Bystrolyotov gained entry to confidential dispatches, inner memos and state secrets and techniques. His work provided Stalin a uncommon glimpse into the inside workings of Europe’s ruling elite. However when The Nice Terror rolled round in 1937, none of it mattered. He was arrested, sentenced and dispatched to the Gulag, callously tossed apart by the system he had served with such distinction.

Walker emphasises:

the historical past of the illegals affords a neat reflection of the story of Russia itself. The early programme, with its hovering ambition, its obsession with subterfuge, and its disregard for the well-being of people, holds up a mirror to the fiery utopianism of the early Soviet Union.

Did the Chilly Battle actually finish?

These had been individuals anticipated to fade into enemy territory, sacrifice their identifies and stay double lives, all in service of a revolutionary imaginative and prescient. However by the point the Soviet Union spluttered to an ignominious halt in 1991, that dream had lengthy since died.

As Walker reveals, a lot of the operatives who adopted within the footsteps of Bystrolyotov weren’t darkly romantic infiltrators scaling embassy partitions or charming secrets and techniques out of countesses. They had been “sleepers” – usually environment friendly, sometimes incompetent – mixing quietly into Western cities and suburbs, awaiting a name to motion that, in lots of instances, by no means got here. The glitz had given approach to the grind.

The People ends with Phillip and Elizabeth, the couple based mostly on Bezrukov and Vavilova, gazing out throughout the Moscow skyline. Two weary spies coming in from the chilly, they’ve returned to a quickly unravelling motherland that won’t perceive – not to mention recognize – the sacrifices they’ve made within the service of its ideology.

As Walker found, Berzukov, when he isn’t being paid handsomely by an oil firm, now lectures in worldwide relations at considered one of Russia’s most prestigious universities. Vavilova, fittingly sufficient, now writes spy fiction.

But in actual life, the story doesn’t finish fairly there. Below Putin, a former KGB officer who reduce his enamel within the tradition of espionage, Russia’s intelligence companies have returned to the illegals programme with a renewed sense of objective (although stripped of the ideological zeal that after propelled it).

Walker is cautious to not bask in idle hypothesis, however he factors to forcing proof suggesting the illegals programme has advanced moderately than vanished. Excessive-profile assaults on UK soil – together with the poisoning of kind spy Sergei Skripal – counsel Russian intelligence businesses stay prepared to function far past their nationwide borders.

In the identical breath, Walker describes what could be termed the digital flip of the illegals programme. Within the place of suburban sleepers decoding radio indicators, Russia has backed groups of on-line operatives – “troll illegals” – tasked with wrecking havoc throughout Western social media platforms.

These paid brokers don’t collect intelligence a lot as sow discord. They stoke tradition wars, amplify political divisions and undermine belief in democratic establishments. Walker affords Russia’s meddling within the rancorous 2016 American election as an illustrative working example.

In Putin’s cruel autocracy, secrecy has as soon as once more grew to become a advantage – and the spy, removed from being a dusty relic of the twentieth century, is as soon as once more a logo of nationwide energy.

In that sense, The Illegals isn’t just a historical past of espionage. It’s a well timed reminder that, at the very least for some, the Chilly Battle by no means actually ended. It simply burrowed deeper underground.