Yiddish is a well-known presence in modern English speech. Many individuals use or a minimum of know the that means of phrases like chutzpah (audacity), schlep (drag) or nosh (snack).

These phrases have been absorbed into English from their authentic audio system, jap European Jews who migrated to Britain within the late nineteenth century, by way of generations of dwelling in shut proximity in areas like London’s East Finish.

Linguistics students have even theorised that components of a Yiddish accent could have influenced the cockney accent because it developed within the early Twentieth century. Phonetic evaluation of cockney audio system recorded within the mid-Twentieth century means that East Enders who grew up with Jewish neighbours spoke English with speech rhythms typical of Yiddish.

A particular pronunciation of the “r” sound is believed to have originated amongst Jewish immigrants and unfold into the broader inhabitants.

The Yiddish music of London’s East Finish introduced collectively the Yiddish language and Jewish tradition of jap Europe with the raucous, irreverent type of the cockney music corridor. Theatres and pubs overflowed with audiences wanting to see the immigrant expertise in Whitechapel represented in all its perplexity and pathos, with an excellent measure of slapstick comedy.

A Yiddish music corridor tune from round 1900 jokes that East Enders dwell on “poteytes un gefrayte fish” – a Yiddish model of the cockney staple fish and chips. The tune lists the numerous novelties that immigrants encountered on arriving within the metropolis: trains operating underground, ladies carrying trousers and other people talking on telephones.

Yiddish music corridor tune ‘London hot sikh ibergekert’ (London has turned itself the other way up) carried out by the creator’s (Vivi Lachs) band Katsha’nes.

Yiddish was additionally the language of road protest within the Jewish East Finish. Through the “strike fever” of 1889, when employees all through east London have been demanding higher pay and dealing circumstances, the Whitechapel streets resonated with the voices of Jewish sweatshop employees singing:

In di gasn, tsu di masn enjoyable badrikte felk rasn, ruft der frayhaytsgayst (Within the streets, to the lots / of oppressed peoples, races / the spirit of freedom calls).

This tune was penned by the socialist poet Morris Winchevsky, an immigrant from Lithuania who spoke Yiddish as a mom tongue however most well-liked to put in writing in literary Hebrew. In London he switched to writing within the vernacular language of Yiddish so as to make his writing extra accessible to immigrant Jewish employees. The tune turned a rousing anthem in labour protests throughout the Yiddish-speaking world, from Warsaw to Chicago.

The decline of Yiddish

But from the earliest days of Jewish immigration to London, the Yiddish-language tradition of the East Finish was a spotlight of tension for the Jewish center and higher class of the West Finish. They regarded Yiddish as a vulgar dialect, detrimental to the combination of Jewish immigrants in England.

Whereas they supplied vital philanthropic help for immigrants, they banned the usage of Yiddish within the academic and spiritual establishments that they funded.

In 1883, budding novelist Israel Zangwill was disciplined by the Jews’ Free Faculty, the place he labored as a instructor, for publishing a brief story liberally sprinkled with dialogues in cockney-Yiddish.

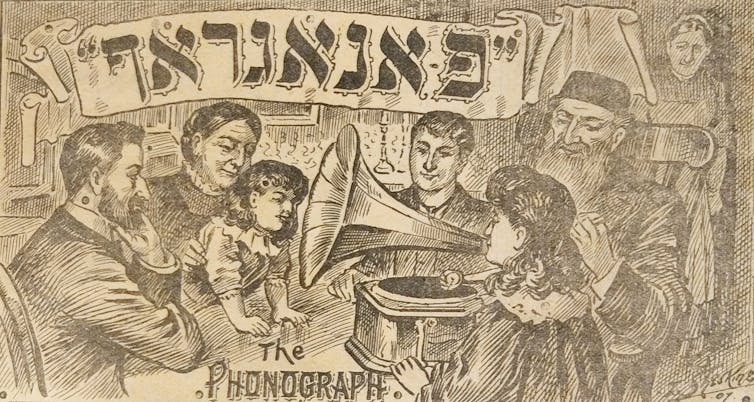

Yiddish-language newspapers like Der Fonograf flourished within the early Twentieth century East Finish.

Courtesy of Jewish Miscellanies web site.

Jewish writers of the postwar interval have been haunted by the sense of a misplaced connection to the Yiddish language and tradition of earlier generations.

In his novel The Lowlife (1963) the narrator’s vocabulary is peppered with Yiddish phrases. However these fragments are all that continues to be of his hyperlink to the East Finish the place he was born. When he returns to those streets, he feels that “my too, too solid flesh in the world of the past is like a ghost of the past in the solid world of the present; it can look on but it cannot touch”.

Yiddish in London as we speak

If you happen to stroll by way of the north London neighbourhood of Stamford Hill as we speak, you’ll hear Yiddish on the streets and see new Yiddish books on the cabinets of the native bookshops. Though they don’t have any connection to the Victorian Jewish East Finish, the ultra-orthodox Hasidic group who dwell there converse Yiddish as their first language.

And for a youthful technology of secular Jews, Yiddish can be buying a brand new attraction. They appear to previous traditions of Jewish diasporism to forge an id rooted in language, tradition and solidarity with different minorities slightly than nationalism.

London is one centre of this worldwide revival: the Associates of Yiddish group established within the East Finish within the late Nineteen Thirties is now flourishing in its modern incarnation because the Yiddish Open Mic Cafe. And Yiddish is as soon as once more a language that anybody can study.

The Ot Azoy Yiddish summer time college is in its thirteenth yr, and new Yiddish language colleges are thriving, together with east London-based Babel’s Blessing, which teaches diaspora languages together with Yiddish and affords free English courses to refugees and asylum seekers. The annual Yiddish sof-vokh hosts an immersive weekend for Yiddish learners.

Yiddish tradition too is being rejuvenated. Tasks now we have been concerned with embody the Yiddish Shpilers theatre troupe, the Nice Yiddish Parade marching band, which has introduced Winchevsky’s socialist anthems again onto London’s streets, and the London band Katsha’nes, which has reimagined cockney Yiddish music corridor songs for the twenty first century.

If Yiddish was as soon as reviled as a debased, slangy mishmash, stuffed with borrowings and variations, it’s exactly for these qualities that it’s celebrated as we speak.